Womb for Rent – By Ayelet Negev

Womb for Rent

7 Days

By Ayelet Negev

The artist Miri Nishri who was orphaned at a young age and experienced her fare share of bereavement and traumatic miscarriages, sent out a photo of fetus inside wooden box to 300 celebrities demanding they acknowledge their paternity. Bill Clinton, The Pope, Daniel Barenboim and the Dalai Lama refused to participate, but Natan Zach, Yoko Ono, Moshe Kupferman and Amos Oz adopted the baby with their own artistic response. Gimmick or Art? The findings are below.

Every week the court system presides over issues of paternity, in favor of women who struggle to get men to accept responsibility over their paternity. A DNA test will determine if the men in question will be responsible for the child’s needs until he or she turn 18. Miri Nishri transported the discussion from the courthouse and into the art world. Over the course of two years she addressed not one but 300 different people with the question: “Will you acknowledge your paternity of the child? And carry out the full extent of the responsibility as a result?” She confessed ahead of time that no DNA testing had been conducted but stated “it’s likely that direct contact with fertile material, yours included, brought about the birth of the child.” She attached a wooden box with a photo of a fetus folded up inside a womb to her claim.

Among the defendants was Bill Clinton (who was both cautious and experienced enough to not respond to the letter), the Pope (who’s personal secretary confirmed the package had arrived but refused to address it), Prof. Stephen Hawking, the conductor Daniel Barenboim and the Dalai Lama who each refused to respond. Roberto Benigni’s secretary announced that the director would not be able to respond because he was busy directing his new film. Among the Israelis that were asked to acknowledge their paternity was the author Amos Oz, the poet Natan Zach, Kneset member Yossi Sarid, the journalist and critic Adam Baruch, Prof. Asa Kasher, the journalist Dov Elboim and Rafi Peled, the CEO of the Israel Electric Corporation.

The address on the adoption forms led me to an apartment crammed with things on the top floor of an old building on Bugrashov Street in Tel Aviv, but the woman who opened the door didn’t look like someone who’s natural state would be to demand paternity from the rich and or famous: “I’m pretty shy in my personal life,” admits Nishri. “There’s a divergence between who I am as a person and the Miri who demanded their paternity be recognized. It was under the guise of her character that I was able to di things I normally wouldn’t do.”

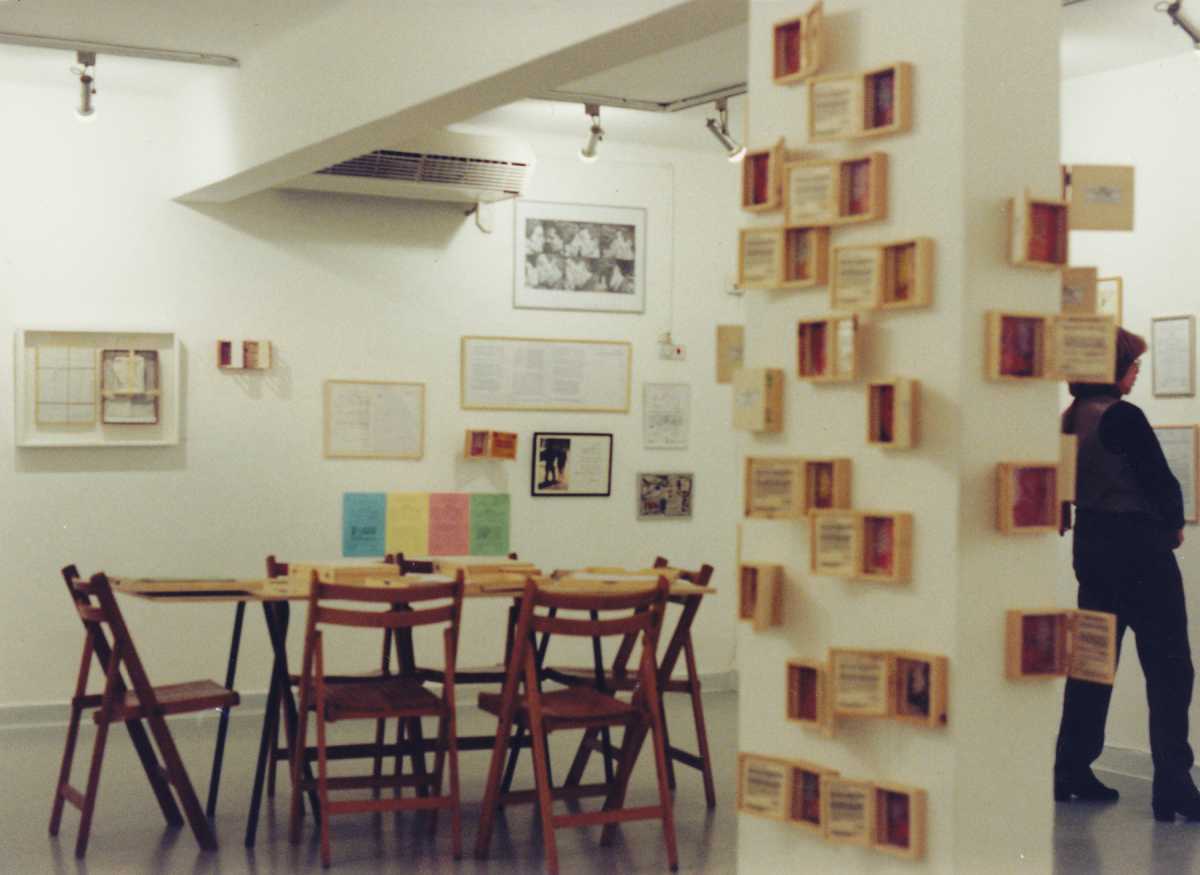

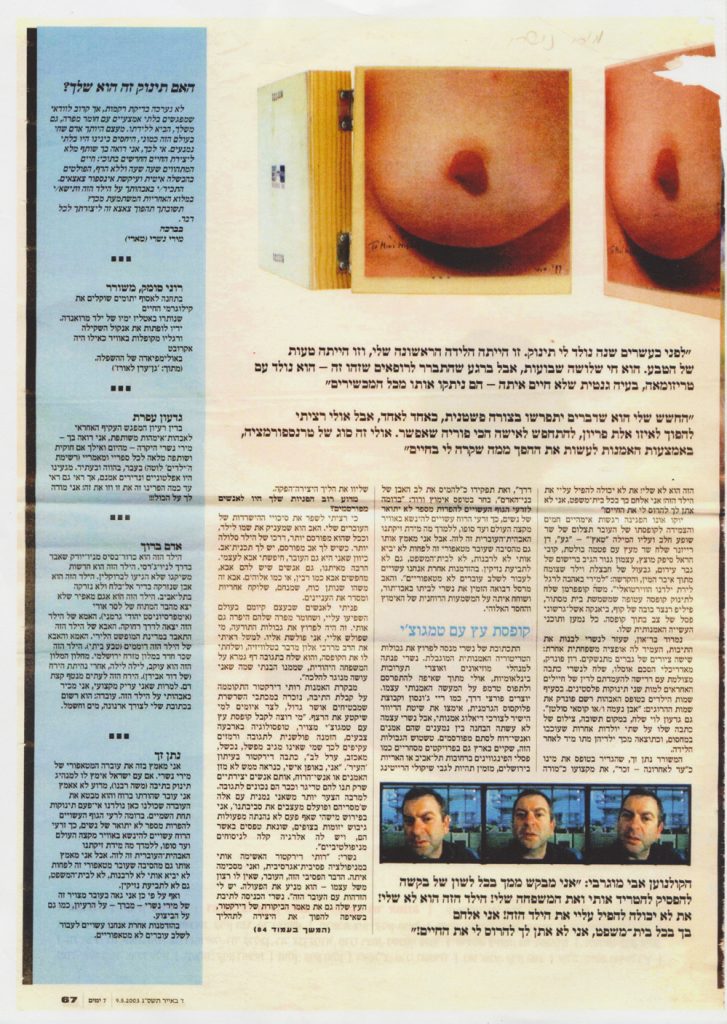

‘Is This Your Baby’, is the name of the artistic project, in which Nishri sent little wooden boxes with a picture of a fetus, an accompanying letter and different color forms: a pink form for declaring paternity, a yellow form to deny paternity, a pink adoption form and a green and white form – for those suggesting a different familial option. ‘Miri – Embryo Distribution’ was stamped across the box, and Nishri added the Virgin Mother name Mary to her own name, alluding at the pregnancy of Jesus’ mother that involved no human touch. About 160 people responded to her of the 300 that were approached, and Nishri displayed the array of responses – personal, literary and experiential – at the Kibbutz Gallery in 2000.

This week a special album will be published, a wooden box similar to the one that was sent out, that includes photos of the works and their response forms. The collection, designed by Itamar Weksler, was produced by Michael Kesos Gdalyowits of ‘Art for the People’ (Omanut Laam), a publishing house that publishes unique artists’ books. Nishti’s book is the second book in the series, following a book of works by Atsmon Ganor, and is sold at the Kibbutz Gallery and at the museum stores.

What drew you to distribute so many fetuses?

One of my fantasies as a teenager was to have a lot of kids, a different child from each man; here I tried having children with 300 different men and women.

Are you the metaphorical mother of these 300 fetuses?

I’m also the mother, and also the fetus itself. I identify with this creature, which is both defenseless and underdeveloped, a potential human creature, a stillbirth that may or may not survive, who’s reliant on the way his surroundings respond to him, he viewer also decides whether he’ll live or die. I can’t birth him, just as I wasn’t able to birth myself. I feel like I’m not ripe yet, that I haven’t been born yet, and there’s something tempting about being in a ‘pre’ state, an ongoing heavenly state, when you still haven’t experienced any disappointments, and all your dreams can still come true. The moment I started identifying with the fetus, it turned into something I couldn’t stop dealing with. I look at it as some sort of self-portrait done in a million variations.

Nature’s Mistake

Miri Nishri, originally Rosenthal, was born in 1950 in Bogota, the capitol of Colombia, which is where her parents migrated to from Europe after the holocaust. “My father was an engineer, he owned a factory, but in Colombia he was a refugee and my parents opened a bakery. They planned to get rich then move to Israel, and started a coffee business, but then my father was run over by a coffee truck.”

Her father was badly injured in the accident, his internal organs were damaged and he never got back to his former self. To help with the income, her mother rented out a room to a widow and her three daughters. Through them I was introduced to the Christian icons, and I was really into the gold and glittery paintings of Jesus and Maria. In retrospect it heavily influenced her esthetic outlook. The girls were orphans, and always wore black like in the fairytales, and they told me all kinds of scary stories from their macabre experiences. Like, for example, when a person is dying, he sees his entire life flash before his eyes. On the eve of my birthday, I lay in bed and imagined m father’s life passing before his eyes, I could really see everything the girls told me about. The next day – it was almost a year after my father had been injured in the accident – I wanted to sit on his lap, like I always did, but he said he wasn’t feeling well and wanted to rest. He never woke up. That day, my 7th birthday, which was supposed to be a joyous day, turned into a nightmare.”

The devastated mother returned to Israel in 1958 with her two daughters and settled in Ginegar. Miri, the youngest daughter, felt out of place: “I was an outsider on several levels: I wasn’t born in the kibbutz, I was an orphan and an immigrant. I refused to speak Spanish, I simply didn’t respond when anyone spoke to me.” She served in the army as a teacher and married Moshe Nishri, a fellow kibbutz member, her high school sweetheart. At 23, they left the kibbutz and moved to Tel Aviv, she studied structural engineering, and later at age 31, started studying at the Midrasha School for art. Her first exhibit in 1981 included video installments, drawings, sculptures and photographs. She currently works as an art instructor, teaching at high school, the Tel Aviv museum and other settings.

Her 14-year-old son, Nimrod, is sitting in the next room, which was born after several years of marriage. As she tries to comprehend where her obsession with fetuses and their strife stems from, she confirms it originated from a traumatic incident she herself experienced: “20 years ago I gave birth to a baby boy. It was my first childbirth, and it was a mistake of nature. He lived for three weeks, but the moment the doctors found out what he had – he was born with Edward’s Syndrome, an untreatable genetic ailment – they took him off life support. In addition I had pregnancies that ended in miscarriages. I was afraid things would be interpreted too simply, too literally, but maybe I wanted to transform into a some sort of fertility goddess, to transform into the most fertile woman there was. Maybe it was a sort of transformation, to create the opposite of what happened to me in real life.”

As opposed to works of art that posses financial potential, Nishri was forced to invest money she didn’t have in creating the wooden boxes, printing the forms, the photos, and the pricey shipping costs. “My kibbutz upbringing got in the way of becoming a savvy businesswoman, and people aren’t waiting in line to buy my fetuses”, she says, her mother donated 10,000 shekels of her own meager savings, and a similar amount was awarded by the Rabinovich Foundation. “I contributed the work of art, this baby, but the creation demanded a lot of attention, it tried to claim blood ties with the viewer and create a ‘scene’”.

To Miri, with Love

‘Is this your baby?’ created intense emotional reactions. “There’s something frightening and alarming about reaching out to total strangers with this kind of claim, that could be interpreted as an act of some crazy woman who steals sperm and taunts men,” admits Nishri. “There were people who were afraid to open the box, they thought it might contain some dangerous materials.”

Nishri addressed the package to people of both sexes. Women responded more metaphorically about the virtual fetus, and commented on the difficulty of comparing a work of art with a living child. Prof. Ruth Gabison interpreted the piece as taking responsibility for the other, even if it isn’t your own child, and the artist Dganit Berst responded with humor: “Miri! Miri! Has the unthinkable – actually happened? Has the heart’s thunder; has passion finally bore its fruit? I will gladly give it my name, if it’s mine.”

“We’ve never had intercourse nor have I donated my sperm for your fertilization,” responded artist and curator Haim Maor, who put down “Married+5” on his adoption form under marital status. “Additionally, I’ve attached a copy of my wife’s ultrasound photo, that proves that she has 2 fetuses (and not 1). The tests confirmed that we’re having twin girls.” Maor returned the box to Nishri with the fetus inside, and pasted a photo of his twins, resting in the womb in a yin and yang shape, and wrote underneath it in Yiddish: “My twins”.

Another person who refused the adoption, Doron Yogev, explained that as “someone who refused every fertilization and stuck strictly to the realm of pleasure, for many years, even if the offers came from the female volunteers at the Kibbutz, even if one or two of them were able to ‘sneak away’ with his sperm, or girls from the canyon who made pilgrimages or the city girls – those of which I had no choice but take to get abortions, and of course my ‘regulars’ – I have to say I took great pleasure in the offer – both the idea and the provocation.”

Prof. Asa Kasher, who son was an officer in the Israeli army when he was killed, did not comply with Nishri’s paternity request, and sent her a lengthy poem which included: “I am a father/ I am Yehuraz’s father/ I am Sarit’s father/ I am Avshalom’s father/…I am the father of humans, not of ideas./…In my view of the world/where I see myself/I see myself as a father/Where I see my way of living/I see my fatherly love/ Where I see my life’s meaning/ I don’t take on any sort of paternity/ I don’t claim any paternity/ I don’t take on any paternity”.

Rafi Peled supplied a more formal excuse as to his refusal to take on any paternal responsibility: “The Israel Electric Corporation must refrain from taking part or financing evens such as these, because it is a public company sponsored subsidized by the general electricity rate paid by the entire Israeli population.” Peled, by the way, is an artist himself, never brought up this argument when initiating art exhibits funded by the Israel Electric Corporation.

“Why do you want a baby, and to have to claim responsibility for it?!” Responded someone who went by the name “Tal”, who said “Nishri was asking for all kinds of legal battles over child support, sleepless nights and all sorts of trouble, and suggested, “instead of distributing fetuses she should think eliminating some.”

Amos Oz kept the fetus for himself and responded with words inspired by the English poet John Donne: “No man is an island – but each one of us is half an island.” Yossi Sarid responded formally and wryly on piece of Kneset letterhead: “I thankfully and thoughtfully received the baby you were so kind as to send to me too”. (I met with a politician who’s name I’ll leave out,” said Nishri, “that told me that it wasn’t clear that is was a metaphor, and that he thought she was referring to an actual fetus. I realized there as no point of addressing politicians because they can only address what exists concretely in reality.”)

Aaron Shabrai, a father of six, wrote: “I accept the baby (although I’m already 60 years old) but I don’t identify with such unnecessary child rearing. People need to be able to make a living, and that they receive justice, also for the Arabs living in ghettos. It’s not an issue to conceive, it’s important that we have a future – work, education, love.” Maya Bejerano sent in a poem, and the director Avi Mugrabi sent in a video he made especially, in which he denies his paternity of the child: “I demand that you stop harassing me and my family! This child isn’t mine! You can’t dump this kid on me! I’ll fight you in court, I won’t let you ruin my life!”

Yoko One put her warm maternal emotions on display and attached a photograph of a breast flowing with milk with the word “touch” written on it, Dan Reisner sent a wooden demon with protruding nipples, Kobi Harel sent a pacifier, Atsmon Ganor responded with a drawing of a male nude with the lily stem and a child growing out of his genitals with the inscription: “To Miri, with love, for the birth of our virtual child.” Moshe Kupferman sent the baby a wrapped up box that could serve as a hiding place, Philip Rantser sent a monkey doll, Bianca Eshel Gershuni sent a sculpture of a turtle inside a box. Every recipient sent a response that corresponds with his or her medium.

Nimrod Bar On, that assisted Nishri with the construction of the boxes, presented her with an alternative familial option: six paintings of men kissing. Ron Pundak, an instrumental figure in the foaming of the Oslo Peace Accords, sent a photocopy of an article demanding to put two soldiers responsible for the death of two Palestinian babies on trial. In the space in the form designated for writing in the child’s name he wrote down the names of the two dead babies: Aben Naama and/or Kusai Sultan.” Gideon Levi also sent a photocopy of an article he had written about two other pregnant women that were held up at a checkpoint and whose babies later dies as a result.

The poet Natan Zach, who identified himself on the adoption form as “male – as of recently,” his profession as a “mentor”, and one who’s job title was to “melt the stone hearts of human beings,” chose a pink adoption form: “similarly to bodily seeds that can fertilize an unbelievable amount of women, the seeds of spirit can also travel from one edge of the world to the other by wind, and teach us how one might forge a paternal bond with this baby. But I will also adopt him because this metaphorical child will never drag me to the Rabbinate, to court, or file any damage claims against me. At some later time we might progress to the point of non-metaphorical fetuses.” Father Marcel-Jacques Dubois invited Nishri to his home in Abu-Tor and they discussed the spiritual meaning of adoption and God’s grace.

Wooden Tamagotchi Box

Nishi’s correspondence is trying to break out of conventional artistic terrain. Nishri reached out to Museum heads and international curators, perhaps hoping to become famous and ride on the wave of the artistic act itself. Groundbreaking artists like Ray Johnson adopted the method of mail art to engage in artistic dialogue, but Nishri never made the distinction between addressees’ who were artists and intellectuals and celebrities. This blurring of lines that exists in Israel in commercial projects like the penguin statues scattered across Tel Aviv or the lions in Jerusalem, makes you wonder about the commercial consideration that went into the creative and production aspect of this project.

Why did you mostly address famous people?

Because I wanted to raise the survival rate of my fetuses. The father is the one who names the child, and the more famous he is, the better off the child’s future is. When you have a famous father, you have a master plan. Because I too am the fetus, I went searching for a father. A lot of us, even people that have fathers, are searching for a father like Rabin or God. A father is a source of strength, that comforts, that takes responsibility and straightens things out.

I reached out to people whose existence in the world influenced me, whose fertilizing components fertilized me as well. I tried to break through the barriers of consciousness, whoever invades my consciousness, I decided to invade theirs. For example, I watched Rabbi Mordechai Alon speaking on television, and I sent him a box. He in response sent me a page of the Gemara that discusses the Jewish family, from which I discerned that what I was doing was apposed to the Jewish law.”

The art critic Ruthy Director was appoled at received the box, saying it reminded her of the chain letters that promise you great happiness, alongside threats of breaking the chain. “Who wants to receive a wooden box with a hand drawn Tamagotchi inside, quadruple multi colored forms, an invasive invitation and around the way hints that those who do not respond are in some way screw ups, failures, disappointments and heartless,” wrote Director in ‘Haeer’. “I, personally, am clearly not the type of artist or intellectual, or creative person who that all you need to do is give them a trigger and they generate a response immediately. Unfortunately, although I belong to the group of people whose ‘actions and words define out society’, I clearly never enjoyed ice breakers when I was in the scouts, I hate filling out forms, and have an aversion to manipulative statements.”

Nishri: “Ruthy Director accused me of passive-aggressive manipulation, and I agree with her. This passive thing, this fetus, that has no will of itself – is what catapulted my actions. I identify with this fetus.” Nishri included Director’s critical article in hopes of transforming the creation into a post-modern never-ending process, with more and more responses.

“During the process of collecting the responses, I realized I was turning into a curator. I felt the need to get out of the musems and galleries, so I sent my baby out into the world, my visrtual baby, to create art that really touches people. My feeling of frustration stemmed from art not having enough power today to do something different and create a real connection with the viewer. I was also caught up with the question of responsibility: does society have the responsibility to nurture art, that way a human being has responsibility for a child that isn’t his or her own.”

Your addressees’ did your work for you. Without them, your work would not exist.

Right. I didn’t know if people would participate in something they hadn’t initiated and I was very pleasantly surprised. I was disappointed when people I expected to respond didn’t, like the Dalai Lama, that refused to participate, or when Deride and Noam Homski returned the box without adding a response. But the disappointment was fleeting, because I felt that a lack of response was also a response. The moment people opened the box, they were engaged. I performed a masculine act, an act of invading their lives, an act of assault, and out of the fetus’s vulnerability, my vulnerability, my shyness, I made a circular act: I told them, hold on to this baby for a moment, and then I left it with them.

Event the Plants Die

‘Is this baby yours’ isn’t the first time Nishri’s tackled the issue of fetuses. She exhibited a series of sketches depicting an unborn child clinging to a prison bars at the ‘Mabat Gallery’ in 1993. “The baby in Nishri’s work will never get to breathe his first breath”, wrote the poet Efrat Mishori, her friend, in the exhibit’s catalog. “The baby can move left and right and up and down but can’t make his way out, to be born, similarly to the Gods that destined Sisyphus to constantly push the boulder up the mountain, Nishri destined her baby to constantly struggle with being born.”

Another exhibit, titled ‘Water Breaking’ was shown at the Yanko-Rada Museum in Ein Hod in 1996. She displayed earth-toned babies trapped inside translucent air pillows on the floor. In a series of works she titled ‘Bearing Country’, she displayed a photograph of her son Nimrod laying in the bathtub, with a toy soldiers with guns strewn across his bare chest. In other photos naked girls can be seen dreaming about dead soldiers, or a pair of furry dog slippers submerged in water inside a sink, appearing like drowned dogs.

Nishri, who got divorced six years ago, now lives with her son. “We were together for so many years, that it felt like tearing to siblings apart. It was a breaking point for me because I hate goodbyes, I’m static, I’m like a rock at sea, the tide crashes around me, and I don’t move unless someone moves me. I was raised on fairytales in which the princess lives happily ever after, and about long lasting romance. I’m not a feminist, and I would love to be a woman who was taken care of by someone else if I could. I was suddenly kicked out into the world, like a baby forced to be born. I didn’t want any changes, but changes haunted me, and since then I’ve been learning how to live in the moment.”

How would you react if someone were to actually leave a baby on your doorstep?

I would give it up for adoption. I don’t think I would raise it, it wouldn’t survive at my place, and even my plants die. But if someone were to leave a work of art on my doorstep I would adopt it.

Her fetus looks at times like it’s dead or dying. “I’m also somewhat peculiar, and I have a warm spot for people with peculiarities. In art what’s interesting is the defect, the thing that doesn’t quite work out. If I lived in Ramat Aviv Gimel, surrounded by people who buy designer clothes and adhere to what’s ‘in’ and ‘out’, I probably would have felt more of an outsider. Where I live it’s very acceptable to be peculiar, most artists are.”

She’s living on borrowed time, at the end of the year she’ll have to vacate the art studio, which also acts as her apartment, and return it back to its rightful owner – the Tel Aviv Municipality. “I don’t own anything and I never inherited anything because I grew up on a kibbutz.” Life is very hard on her and sometime she would like to go back to a fetal state. A huge pile of unpaid bills rests on the shelf: “I’ve taught myself to disregard and not think about the future. I live day to day, and I ignore things that should worry me, because I don’t have a solution for them.”